Adachi and Shimamura's Second Season

An essay by Audrey of the joystick system

Revealing and analyzing the plot of Adachi and Shimamura's never-yet-released second season of anime.

TL;DR:

Adachi and Shimamura, the yuri light novel series by Hitoma Iruma, is extremely good. The currently serialized manga adaptation by Yuzuhara Moke is also good. The anime is good too, but not finished.

The novels go some rather surprising places, and this essay is about those surprises and how Adachi and Shimamura, quite unexpectedly, proves itself a very unique series quite unlike many others in the yuri genre.

Mainly because it's secretly also science fiction.

Video version:

Text version under the cut. Feel free to watch or read or read along while listening to the video version!

Table of Contents

Prologue: Triviality & Psychology

Despite not having read a single word that Hitoma Iruma has written, I think I’ve been convinced, with relative certainty, that he’s probably a pretty good writer.

The English versions of his work that we have read, which are written by other people, based on his novels written in Japanese, that we haven’t read, give the impression that his novels are pretty good.

Of course, the specific work we’re here to discuss today is Adachi and Shimamura, but of what little else we’ve read of his work, mainly the first chapter of the Bloom Into You spinoff novels, there’s a consistent focus on introspection and careful characterization and articulation through all sorts of details, both trivial and otherwise.

This may sound arrogant, but I knew early on that I was talented.

When I say “talented,” I mean that I can get results when I work really hard and that I can maintain those results, too. I think I understood the value of those two things much sooner than the other kids.

Thus, I didn’t mind that my after-school schedule was full of lessons. There were ikebana classes, calligraphy school, piano, cram school, and once I was a third year in elementary school, swimming lessons, too. I was considering taking on English speaking classes next. I pretty much took anything available to me. As a kid, I felt lucky that I was even allowed those choices.

Even a child could see that that my house was a respectable one. We had a lacquered gate, a side door for the help on the left side, and many tall trees in our garden. The surrounding walls were tall enough to prevent anyone from peering inside. Our house was bigger than the entirety of the light-green apartment complex across from us. In addition to my parents and I, my grandparents on my father’s side and their two cats lived there. It was quite a lot of space for so few people.

Growing up in that house, I knew I had no choice but to be talented. No one actually said as much, but I knew instinctively that it was true. As long as I kept moving with purpose and produced good results, my parents never seemed upset. What parents wouldn’t be happy to have an exceptional kid?

Bloom Into You: Regarding Saeki Sayaka, Vol. 1

by Hitoma Iruma

Translated by Jan Cash and Vincent Castaneda

Published in English by Seven Seas in 2020

The first pages of the Sayaka novels open with Sayaka describing her school curriculum and extracurricular activities, her awareness that she’s a gifted student, and that she’s incredibly committed to being one, so much so that she rarely quits something. She is devoted.

And this characterization informs the rest of the work quite readily, as Sayaka finds herself first annoyed by another girl at her swim practice, who to her, appears not devoted.

Devoted perhaps, not to swimming, but to Sayaka herself. And then her first lesbianic encounter with that same girl results in panic, in her running away, in her quitting.

Quitting for the first time she can remember.

And her quiet surprise when her parents just accept that.

All this is told to us, in prose, in monologue, it’s delicate and psychological and intriguing and it leaves us wanting to know more.

And yet somehow, we read all this, were fascinated, and then our attention span burned down around it and we forgot about it for a year or two.

So, yeah, that happened. And we also forgot about… until one day very recently I, Audrey, decided to wrangle this mess of a brain and have us settle down to read it… Adachi and Shimamura.

Part 1: The Adashima-daptations

1.1 Anime vs Manga vs Light Novel

Most of y’all know Adachi and Shimamura for being an anime. And, that’s fair, I guess, it is an anime after all. But it’s also an adaptation, as most anime are. And specifically an adaptation of a novel, or a series of novels, the first four of them at least.

Those four novels are only the first act of the story. There’s now ten, with at least two more planned, and we’ve read eight of them, and I have opinions. So you’re going to hear them, because someone has to. Unless you don’t want to, and then you can leave, I guess. We are fine with people leaving. Anyway.

Concerning the anime, we have some feelings about it. Our overall opinion is that it’s good. It’s a pretty good anime, it’s a competent adaptation, and we don’t really have a lot of complaints as to its quality in either of those respects.

It’s not a particularly lavish production, nowhere near as technically impressive as Bloom Into You (which is one notable example of “probably about as close as you can get to a KyoAni level work without being from KyoAni”) but it’s pleasantly storyboarded, elegantly scored, and overall perfectly watchable.

It’s good enough to recommend as an entry point into the story (although the Moke manga is the far better adaptation), but woefully insufficient as a substitute for it. Partially for the obvious snag that it ends before the relationship gets going, and there’ll likely never be a second season.

But there’s also some speedbumps that have, somewhat unavoidably, arisen from adapting the story to a visual medium.

1.2 Shimadensity

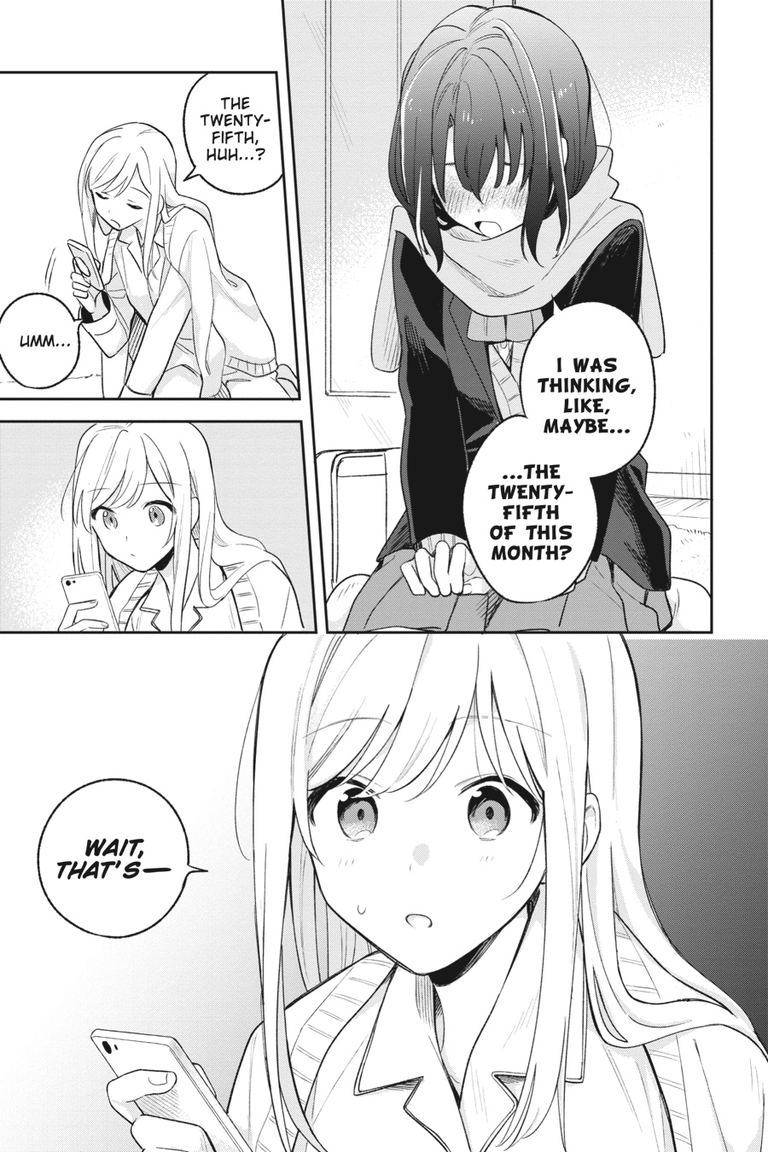

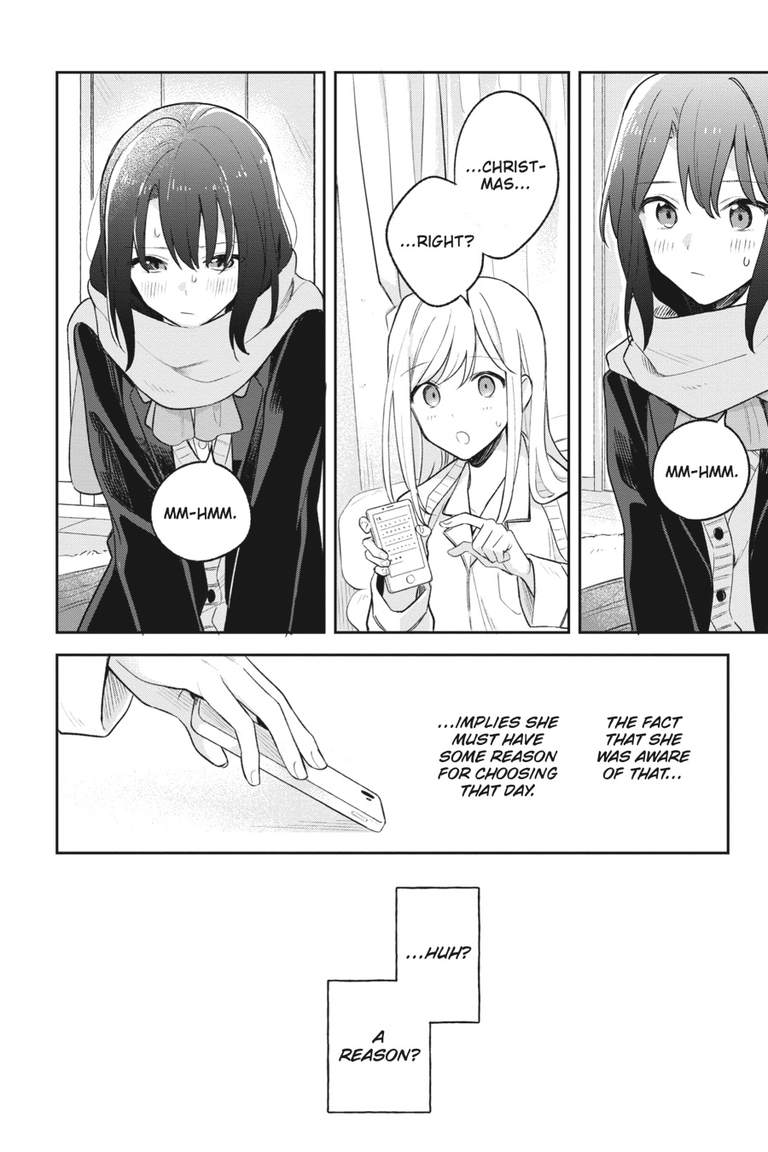

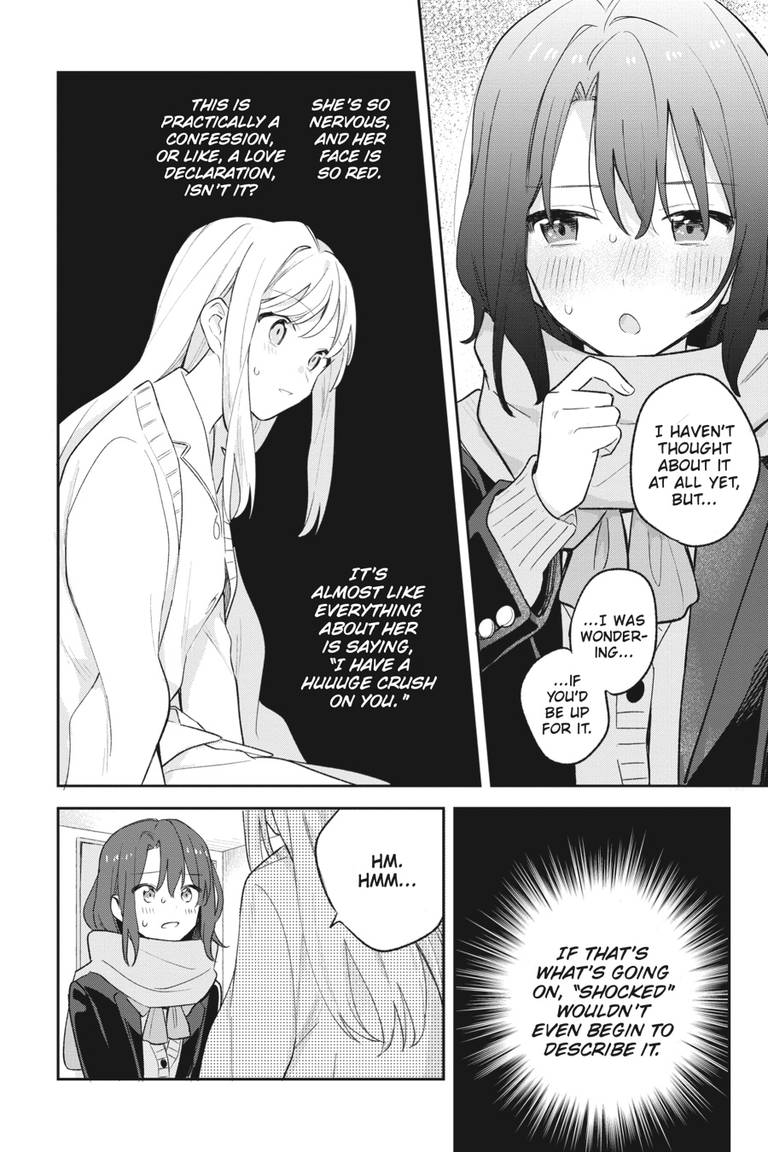

When the anime aired, the thing I most remember is people being confused as all heck why Shimamura was so… dense.

That is to say, blind. A blind blonde, an unnatural blonde at that, being blind to the obvious homosexual before herself, being extremely homosexual towards her in her presence and drinking mineral water, which, as anyone who’s seen the film Heathers knows, is a universal signifier of homosexuality.

And, well, you see, there is an answer to that. Shimamura is not blind whatsoever.

She knows something is up with Adachi, and it’s not as if she’s not pretty nearly drawn the conclusion that Adachi is attracted to her, but she’s just sort of averted her eyes from it.

She’s decided, albeit somewhat subconsciously, that thinking about Adachi being gay is troublesome. Answering the question of “why Adachi wants to hold my hand, wants to be so close to me,” and all that, isn’t a path she’d like to take, and so she just ignores it.

Shimamura’s gotten through life this way, by not thinking too hard about it. Just going with the flow, letting everyone around her take her wherever, putting up a path of least resistance through life. She finds forming genuine, lasting connections with people difficult, and doesn’t really feel very strongly about most of her peers.

But she also feels that she needs people, anyway, so she masks through it, politely smiles, and lets her relationships just happen, come and go like the waves. This does bother Shimamura, if for no other reason than that she finds it tedious and tiresome, but she just kind of rolls with it anyway.

Meanwhile, Adachi is explicitly an introvert to the extreme, and not in the Bocchi kind of way, where she wants to make friends but can’t; no, Adachi straight-up doesn’t want friends. She finds friendships burdensome, to the point of being soul-crushing.

An anecdote in the novels has Adachi describing how, in elementary school, she made an honest attempt towards being more socially active, but found that each new friend she made felt like another chain on her soul.

But these forced friendships weighed down on me, suppressing my emotions, erasing all my imperfections. Whenever one of them spoke to me, I had to craft a fitting response and keep the conversation going. No part of this was genuine; I just parroted whatever I heard other people saying.

Every time I repeated this process, I grew restless. And every time I gained a new friend, I boxed myself in further, closing off my exits.

But then one day I threw it all in the trash and walked off without them…and that was the day I noticed just how freeing it felt. All I needed was a single breath of fresh air to finally realize that I was meant to live my life alone.

Adachi and Shimamura Volume 4 (Chapter 3: The Moon and Courage)

by Hitoma Iruma

Translated by Molly Lee

Published by Seven Seas in 2021

Eventually coming to accept that, at least in her view, she was not built for close relationships with other humans.

To put it simply, it’s not a skill issue. She just doesn’t care for the grind.

1.3 They Who Don't Remember Your Name

In middle school, she comes off towards her peers as an ice queen, and there’s this really really interesting chapter- the first chapter, in fact, in the fourth novel, where Adachi is described from the perspective of someone else. An unnamed fellow student, with whom she is delegated to work the school library counter, who tries and fails to form a connection with her.

And this student’s description of Adachi is fascinating. Adachi is described as someone who, in step with her desire to eschew friends, is seen by the student body as seemingly unattainable. And this student is startled, then elated, to have the opportunity to even sit near this person.

But Adachi, unconscious and undesiring of her semi-celebrity status within the school, deflects all attempts to break her shell, and so there this unnamed student stays, stays looking, stays admiring.

And then one day this girl, this unnamed student who we never again hear of, who has no significant characterization to speak of, no importance to this story other than to be a lens through which we see Adachi- happens to run into Adachi once again at the beginning of their high school’s second semester, and takes the opportunity to say

“Thank you.”

For something that Sakura Adachi didn’t know. Didn’t see. Couldn’t feel. Didn’t realize. Something so incorporeal to her, yet so powerful to this one peer of hers, as having been allowed to be in proximity to her, to have a memory of her that none else can claim to have.

And Adachi doesn’t get it, and can’t possibly have it explained, and it’s just… that’s it, really. That’s just that chapter.

It was gut-wrenching to read, because it tapped deeply into a specific desire that’s been stuck within us for a long time, that we’ve previously found it… really hard to articulate without sounding weird, or creepy, or wrong.

The desire to know how we were seen, the impact we’ve made on people we crossed paths with whose names we don’t know, whose faces we’ve forgot, or whose lives just briefly overlapped with ours at one time or another

to know if they’re okay, to know if they even remember us, or, the person who we used to be, whoever that was, to be able to affirm that those connections, however tenuous, were important.

And just like… yeah, I don’t know. I don’t know if what I’m saying even makes any sense, but those many little encounters, those small moments that made us who we were

have left us conscious of dozens if not hundreds of possible branches in this life, that could have butterfly effected us somewhere completely different from where we currently are, and we can’t know, and we can’t say

but it’s just it, that basic feeling of I wonder how you’re doing, I wonder how life could have been if we’d followed after you, I wonder if you think about me too.

And that desire to achieve closure, something articulated, actualized, in this unnamed girl saying thank you, and at the same time, saying goodbye. To another Sakura on the wind.

1.4 Adachi Recollection

These events are not adapted in the anime. They are not adapted in either of the manga adaptations.

But there is such significance to this anecdote, such immense weight that is given to this random no-name and her view of Adachi, a story about Adachi to which Adachi herself was nearly entirely oblivious.

But then later in one of the most pivotal moments of Adachi’s character arc when a shady fortune teller convinces her to do something about her friendship with Shimamura before they drift ever further away, and she remembers that girl,

Every now and then, I thought back to this one time in junior high when I worked as a library assistant. There was this girl—I couldn’t remember her name or even what she looked like, but she asked me if I had any friends. At the time, I told her I didn’t, and that I was fine with it…but looking back, I couldn’t help but wonder why she asked me that. Was she going to offer to be my friend?

Even then, my answer would have remained the same. I would have told her I didn’t need any friends. But part of me regretted how that interaction played out. Part of me felt that we should have talked it out first, like actual human beings, instead of me one-sidedly slamming her with rejection.

With that in mind, I didn’t want to add to my list of regrets. I couldn’t keep sticking my head in the sand. No, I was going to take action. And if I ended up regretting that, then so be it.

Adachi and Shimamura Volume 4 (Chapter 3: The Moon and Courage)

by Hitoma Iruma

Translated by Molly Lee

Published by Seven Seas in 2021

And this is such a hugely emotional payoff. Adachi did remember. That girl did affect her life. Even despite Adachi’s efforts to refuse connections, still, such a trivial interaction still made her who she is, still contributed to altering the course of her life, and that’s just… y’know, like, gosh.

This is so fucking cathartic to think about, y’know? Even if that person you remember, you wish you could have known, isn’t thinking about you, barely remembers you… you still were there. You still did something for them. Even if it was just being there, even if your feelings didn’t reach them right then, even if even if even if.

The fact that you crossed paths with them, alone, is significant.

It’s that affirmation of that fact that I see in this small, insignificant seeming novel-only plot beat, from which I feel so much meaning is exuded, and, why it's a shame it was excluded.. It may have seemed trivial, seemed unimportant, and seemingly that’s why every adaptation adapted this out,

but that triviality is precisely what is so important about it.

I cannot exaggerate enough when I say that I feel something essential is lost by this piece of story being discluded from every other version.

And that’s really the curse of adapting Adashima, in general. There are so many other details of the characters and story, too numerous to list, that the prose takes time to explore and develop and clarify, that would be tedious to elaborate on in an anime or a manga, and are thus cut.

And rightly so, for the sake of telling the story economically in those mediums, but what is lost as a result is the essential psychological depth of this narrative. And yes, it is a psychological narrative. A cerebral one, even.

Yes, it’s true. Adachi and Shimamura is a calmer, gayer, Kaguya-sama.

And that’s why

Shimamura is so

fucking

dense.

And why Adachi and Shimamura, is so, fucking, dense.

Part 2: A (mostly) calmer, gayer Kaguya-sama

2.1 Cold War of Gay Panic

Once you’ve read deep enough into Adashima, there is absolutely no way around it, this is a deeply psychological conflict. The characters’ mental states and attitudes, the things they won’t say, say so much more in this story than anything else. Which is why I think, although the adaptations are pretty good:

The Moke manga adaptation is actually really good, it does a much better job visually illustrating the psychological aspect of the story than the anime does, and, I think, if you’re really allergic to prose but really want to read Adashima, you should read the Moke version.

It’s not a perfect 1 to 1 recreation of the story, no adaptation ever is, but it’s pretty damn up there. Nonetheless, the adaptations are still limited in how far they can go in elevating their versions, and Adachi and Shimamura, the anime, is good.

Just good.

It’s a competent slice-of-life anime and an incomplete romantic drama. And it’s nice to have a visual companion to the story. But as a standalone piece of media, it’s not all that much more. It doesn’t get the time to develop things further, or to get to the things that make Adachi and Shimamura, as a story, something truly unique.

So, I mentioned earlier that Adachi decided she can’t do relationships, of any kind, and you might be thinking, well that sounds like a terrible protagonist for a romance story, and oh gosh you have no idea. Adachi is a total disaster of a human being. And just to drive that point home quite clearly, I want to read this particular quote from volume 5:

Besides Shimamura, the current me had nothing. I was empty.

Were you to peel back my skin, you'd find not flesh and bones, but her. Shimamura.

And yet. And yet. I felt like I might start tearing out my hair soon. Simply allowing my mind to wander caused my eyes to grow wet with tears.

The fantasies I'd indulged in were not based on anything. I knew that. Even so. Even so.

Was it really that wrong, wanting to be rewarded? Wanting your efforts to pay off?

Adachi and Shimamura Volume 5, "Shimamura's Sword"

by Hitoma Iruma

Translated and published unofficially by sneikkimies